There is a disorienting amount of tragedy out there, right now, so it’s hard to know why you wind up fixating on one. But, like so many people who were lucky enough to have been drawn into his orbit, I am struggling to process the sudden loss of Professor Michael Burawoy. It’s an absurd thing to say about someone who was in his late 60s when I started graduate school, but in my mind, he was just always going to be there.

I applied to Berkeley in part because I specifically wanted to work with him. Lots more were pulled in by his magnetic charisma and commitment just at the moment they were abandoned or repelled by flashier, and flakier, faculty. Still, I honestly do not know how Michael wound up reading my undergraduate thesis during my first semester, but when he did, he wrote me a five-page single-spaced memo. I just reread it. He was so generous, of course:

“What an amazing thesis! Intrinsically interesting, well written, analytically astute. It is built on superb field work and an extraordinary wide ranging knowledge of sociology and beyond! I am stunned!”

But Michael understood, so well, that kindness and enthusiasm are the best precursor for demanding more from someone than they would demand from themselves. He walked through the literature my research on dumpster divers seemed to touch upon – urban ecology, social movements, consumption – before, of all surprises, concluding that it really should be about the political economy of waste under capitalism:

“In this view the book would be a sort of manifesto for freeganism that would be about the political economy of waste that would effectively elaborate a politics of waste, bringing out what is perhaps implicit in their practice and gut ideology. That surely is one role an intellectual/sociologist can play with regard to a social movement. I think it would be very exciting to write a book of this nature, although it would require a lot more work.”

He closed, of course, “I would be happy to work with you on this.” What an understatement! I futzed around with a draft unsuccessfully for a year. By year three of grad school, I was miserably depressed and decided to take some time off to live at my parents’ house and work in a warehouse. Michael asked if he could shop my (only marginally improved) manuscript around to presses while I was convalescing. I wasn’t even a student at this point! But he somehow cajoled an editor to take a chance on me. It’s so hard, in retrospect, to know why he even did this, except that he genuinely believed in people and genuinely believed in their ideas, even if they themselves didn’t believe in them.

I always appreciated the Michael, despite his dedication to the craft, recognized the doing ethnography is taxing and tiring; he was not an ethnographic cowboy who felt most comfortable in the field, and always saw the awkwardness it entailed. Perhaps because of that recognition, he made his ethnography seminar into a joyous space. He’d come in, cackling in his special way, nodding his whole body and declaring “Yes… Yes…” when he learned we’d gotten a foot in the door or started to finally figure out what it was that we were actually observing. There were, of course, two-by-two tables galore; every finding had its antithesis, every group its counterpoint.

In 2017, I was coming off of yet another leave of absence. I was convinced my dissertation was in shambles (I was lucky my adviser was wise enough to know it wasn’t, really). But part of what brought me back to Berkeley was the chance – and I thought, almost rightly, the last chance – to teach for Michael’s legendary theory class. I had a series of notes to his lectures that had been passed down by his TAs from the early 2000s. Largely, I could predict his jokes from them. The class was an intricate piece of art, every part honed to perfection. Still, he spiced it up and kept it relevant. At the end of fall semester, he encouraged students to “smoke some ST [Social Theory]” over break and have some “Netflix and Chill.” The students gazed at each other, all wondering, “did he understand what he just said?” Who knew: Michael was both a dinosaur and incredibly good at keeping up with the times. He got away with lines like this because he was so visibly beyond reproach in his relationship with students. And the jokes kept them coming, week after week.

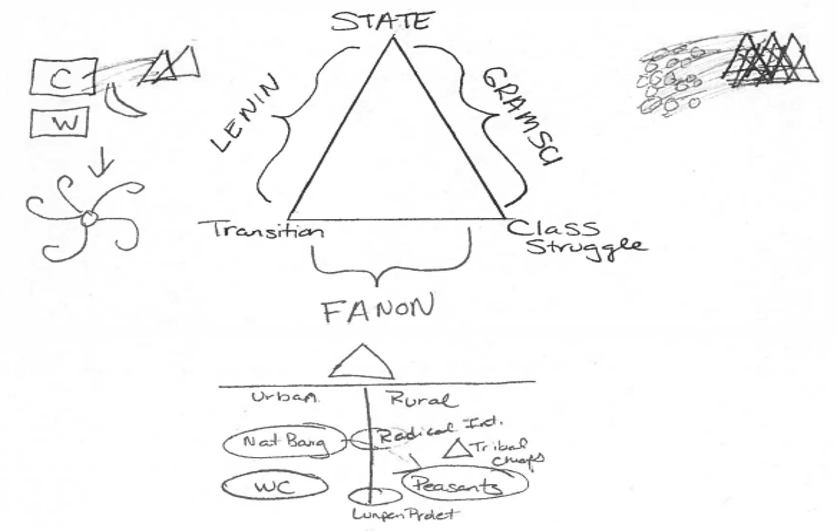

And the pictures! I get that the following image, depicting all of Marxism from Karl himself to Fanon, does not, objectively, make any sense. What the fuck is this octopus that Lenin is contending with in the transition away from capitalism?:

But Michael infused it all with so much meaning. Students strained to decrypt the images, because they were convinced there was some truth within them, which they believed because Michael believed it too. That semester, we were all taken aback by how much our students were struggling: we had homeless students writing papers on their phones while taking BART just to have a place to sit; others were cramming passages from Foucault in between multiple service jobs. He – who had observed the gradual attrition of resources away from public universities and the mounting barriers to our students’ full participation – had, of all of the teachers, the most right to by cynical and frustrated. Instead, he told us, over and over again, “Our students are doing amazing things to be here.” He was so right.

There was never a picket line called by the grad student union where Michael didn’t show up in support. There’s a hidden bit of hypocrisy here, though, because no one was more successful in getting their TAs to break their 20-hour-a-week contract than Michael. Every Thursday, after lecture (and a special open-to-anyone session – Anything Goes [same initials as Antonio Gramsci, coincidence?] – that Michael added and personally led when budget cuts reduced the number of discussion sections led by TAs in the class), we met in his office to Discuss Theory for the next week. He’d break out a selection of exotic liquors he’d accumulated lecturing across Eastern Europe and we’d delve in, deep, into what a War of Position really was and if there’s any resistance to power in Foucault other than Damien lifting his head right before the end of his execution. And then we’d go to dinner, and Michael would ply us with stories about decades of departmental drama. I know I will never offer anything like that to my teaching assistants, and maybe no one should. But those Thursdays were the moments where the existential angst and brutal professionalization of graduate school faded away, and we could convince ourselves that these conversations really were what this whole career was about.

This was the year a new biography came out hyping how Foucault’s experience taking acid in Death Valley shaped his thinking. So Michael took his TAs there (whether we followed in Foucault’s footsteps once we were there, I suppose, will remain a mystery):

He was so funny. The last time I saw him was when he came to NYU to present on his new work on DuBois. He went on a rant about his previous decade “lost” reading and rereading Bourdieu, lamenting that it could have been avoided had it never been translated. Paul DiMaggio, if I recall, piped in to say that translation allowed many people to discover his work. “It should never have happened!” Michael thundered, in that exaggerated tone that explains why, for forty years, lecture halls filled with 200 students twice a week for 28 weeks were enraptured by him.

I’ve already been in a state of unending angst about how the upending of undergraduate teaching by AI means that many of the things that made me love universities will not be there if and when my kids apply. Michael being taken from us feels like such a sudden, brutal microcosm of this draining of wonder from the intellectual world. During our long TA dinners, he’d regale us with stories of a time when graduate students thought having a Marxist ethnographer on faculty would be the leading edge of profoundly transforming universities (and the faculty opposed to his hiring feared the same). I remember one theory discussion where he insisted we simply had to understand how Durkheim’s collective consciousness could bring about social change – because, after all, social theory needed to be liberatory, somehow, or it wasn’t social theory. I think even as the obvious candidates for transformative, structural change faded from view, he still found the possibility in students themselves – that they (in his theory class, a large majority of them community college transfers) could find the answers to their own exploitation, exclusion, and marginalization in a photocopied packet with The German Ideology and Collins’ “Outsider Within.”

I knew everything else was changing but I needed to believe that, improbably, impossibly, he would stay the same.